March 7, 2022

Professor, CEO, Liberal Candidate and Author Mike Robinson on His Latest Book

As a bright 20-something keener, what do you do with a law degree and several other noteworthy pieces of parchment in anthropology?

Well . . . if you’re Mike Robinson, you become the executive director of UCalgary’s Arctic Institute of North America (from 1986-2000), an adjunct professor in what is now the School of Architecture, Planning and Landscape (1997-2011), and CEO of the Glenbow Museum (2000-2007). You then run for the Liberal party in the 2008 Alberta provincial election (and lose), and follow that by becoming CEO of Vancouver’s Bill Reid Gallery (2009-2014), before moving to Powell River, B.C.

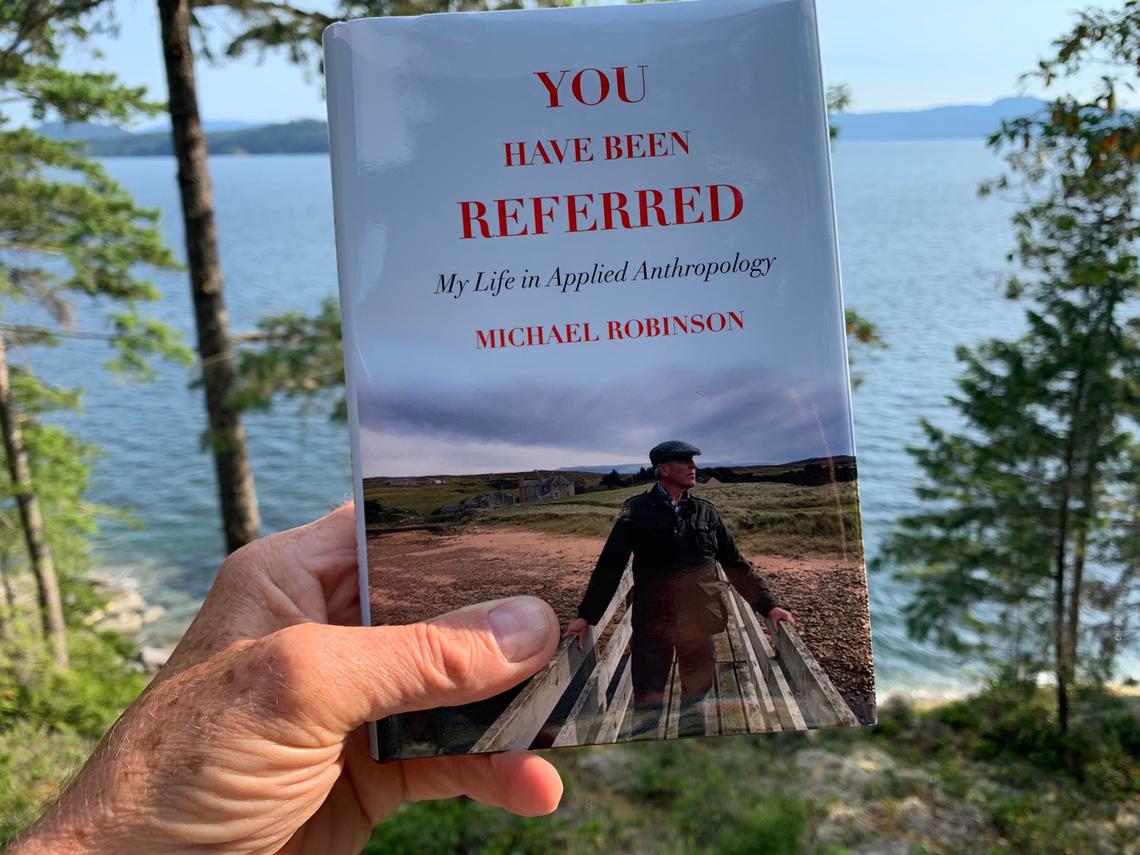

It was there that Robinson penned his most recent book You Have Been Referred. But it’s critical to note that, before this powerhouse began stacking up a prodigious number of high-profile jobs, Robinson worked in Calgary’s oil and gas sector during the rollicking good times in the ‘80s — exactly when his new book begins.

Part-memoir, part-love letter to the land and Indigenous people, You Have Been Referred is, fundamentally, a book about Robinson’s robust and rewarding career and the values that tugged it in myriad directions. Academics, meanwhile, will feel comforted by the book’s three-part structure: thesis, antithesis and synthesis.

What is unusual about this book are Robinson’s anchors to spiritual connections and how they helped shape his life and his career. Underpinning his many adventures, antics and challenges is his lifelong quest to align his values with his many jobs and, ultimately, what happens when they’re out of sync.

In You’ve Been Referred, the level of detail and use of quotes that, in some cases, extend back decades, is staggering. What was your process of capturing and recording such details?

I’ve kept a daybook all my life where I write about what I am doing, thinking . . . sort of the big takeaways of the day. I have about 40 of those books, plus, for decades, I kept separate journals about trips and research projects so I had a lot of material even before I sat down to write this book in 2008. And, for the sections about the work we did in Russia, I drew on a previous book, Sami Potatoes, that I co-wrote at the University of Calgary with my colleague, Karim-Aly Kassam (BA’87), in 1998.

You Have Been Referred, Robinson's latest book

Why did you begin writing in 2008?

After losing the election by 1,180 votes, a buddy of mine said, “OK, go into your cave and lick your wounds for six months.” That’s when I began writing this book, but then an opportunity at the Bill Reid Gallery came along, so the book was stalled.

At the end of those six months of writing, what had you produced?

A series of stories that just seemed to bubble up. But, when I returned to the project, when COVID began and I had left the Bill Reid, it was pointed out to me by those who read the script that it desperately needed structure, that I couldn’t just run the stories all together. That’s when we came up with the three blocks that tied my values to my career.

If someone wanted to write a memoir, what advice would you give them?

No. 1: Block out a chunk of time to write; ideally six months. No. 2: Approach it as a piece of work; be disciplined and write every day. No. 3: Be responsive to the bubble-up type of story and document them as they bubble. No. 4: Structure. The time sequence in a memoir is key, or it will be all over the map. Remember, it likely should start with birth and death and include all the stuff in between.

Endings are often so difficult to write, and yours is a bit of a fantasy. How did that come to be?

Without giving too much away, my challenge was to see if I could write a conclusion that bundles up the gifts of all the people who have played a role in the stories. After all, a memoir is a collection of stories, right?

Elect Mike Robinson

The jobs you had early in your career, before you joined the Arctic Institute, seemed to be frustrating and in conflict with your values; how do you know when things are not aligned?

Much of the work I did in the oil patch (in an environmental and social affairs group with Petro-Canada, and then in community affairs with PolarGas) didn’t go anywhere, so that was frustrating. Secondly, it was difficult working with people who had fundamentally different values and were in opposition to what I was trying to do. My jobs in the patch were to integrate the local environmental and social realities with the projects' technologies, economics and employment potentials.

You likely didn’t use the word “mentorship” when you were a university student or a new grad but, upon looking back, who were your mentors?

I didn’t have mentors, per se. But I had strong influences — some of whom came into my life lightly, others with a thud. Some may have said, “Well, this is what I did when I was confronting that.” Others may have been more blunt and said, “Clearly, you need to get a new job. You need to apply yourself in a different way.” And then, I was lucky enough to have many Indigenous Elders in my life who, by virtue of age and experience, gave me wisdom and advice.

The importance of understanding and living your values is what knits this book together. What values were you raised to follow?

I think values are first learned — internalized, if you will. And at some point they become subconscious drivers … they are just there, in the air you breathe. I was raised in a patriarchy that had a strong ethic of public service. Like some of my relatives, I became a member of the Order of Canada and a Rhodes Scholar. I did both of those things, in large measure, because of the values inculcated in me by my dad, and my uncle, and my grandfather.

What is the significance behind the book’s title?

The title refers to a comment made, “you have been referred,” by a hotel clerk in Vancouver, that resulted in a group of Gwich’in clients of mine from Fort McPherson, and me, being shunted off to another hotel miles away from where we had booked our rooms. Chief James Ross, my Gwich’in pal, told me to be quiet and watch the scene play out. I did, and we were sent off to what James called the “Indian hotel.”