Who Will Help Mom?

Magazine | Fall/Winter 2019 | Who Will Help Mom?

by Mike Fisher

illustrations by Yasmine Gateau

Vivian Coles, 56, gives herself a pep talk as she manoeuvres through traffic in Calgary. The dental hygienist juggles her job with looking after kids at home and attending to her mom, Esla, 76, who has Alzheimer’s and lives in a retirement residence. Today, she’s on the way to take her mom shopping at lunchtime.

“How can I make it a nice day for her?” thinks Coles. “How can I help her focus on things that make her feel positive and grateful?”

Coles started her day at 6 a.m., kicked it off with a coffee, called her mom, rushed to the nearby Fitness Plus for a workout, got home, made sure others in her family had something to eat, grabbed a shower, called her mom again to remind her she’d be there at noon (her mom had already forgotten), got dressed, called her mom again (for whom voicemail is overwhelming) and then jumped in the car.

Her mother was raised by deaf and mute parents in Chile. She was a strong and independent woman, but has had mental-illness challenges throughout her life. More recently, there have been outbursts at her retirement home. Coles is worried that, in time, her mom may have to move to a less-familiar, more expensive facility.

“She needs to feel loved and special,” says Coles. “She isolates herself socially at the retirement home. My kids are seeing that, even when she’s with us and asks the same questions over and over; she’s trying to be part of the family, her little community.”

After shopping, Coles takes her mom back to her room and tells her she’ll be coming back. To end the visit on a nice, positive note, she asks her mom to think of something she’s grateful for.

Her mom pauses, looks up and says: “You.”

She needs to feel loved and special. She isolates herself socially at the retirement home.

— Vivian Coles

Confused over a splintered system of information? Here’s a primer of service organizations to help get you started.

Preparing for a rising tide of seniors

The daily, overwhelming problems that Coles and others like her face are multiplied by millions across the country and swell into every corner of society. We can’t foretell the future, but if we view certain trouble spots through the lens of the work done by University of Calgary researchers, we can gain a better understanding of how to move forward.

The brunt of caregiving for aging and ailing parents usually falls to women. Like Coles, they’re often members of the so-called “sandwich generation,” hard-pressed between parents and children. Unlike Coles, some look after parents who can stay in their own current home, but need help; others combine their households with their parents.

Mike Lang, MSc’15, who is now working on his PhD at UCalgary, launched the web series, Being There: Helping Caregivers See Their Place in the Story, in 2018 with the support of the TELUS Fund. There are more than 8 million active caregivers in Canada, most of whom are unrecognized and unpaid, and this number is expected to double within 20 years, he says.

This legion of unpaid caregivers is growing across Canada as the country braces for a tsunami of aging citizens. The population of seniors — those age 65 and over — is set to surge, boosted by aging baby boomers and increased life expectancy. And many caregivers will soon enough be seniors themselves — if they aren’t already.

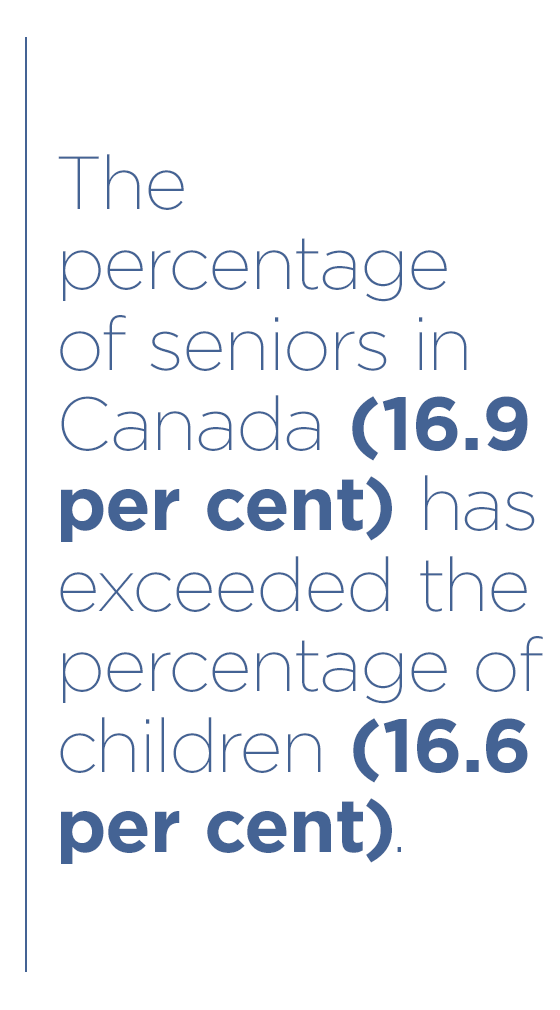

In 2016, for the first time, the percentage of seniors in Canada (16.9 per cent) exceeded the percentage of children (16.6 per cent). There were 5.9 million people aged 65 and older in Canada, slightly more than the country’s 5.8 million children under 14.

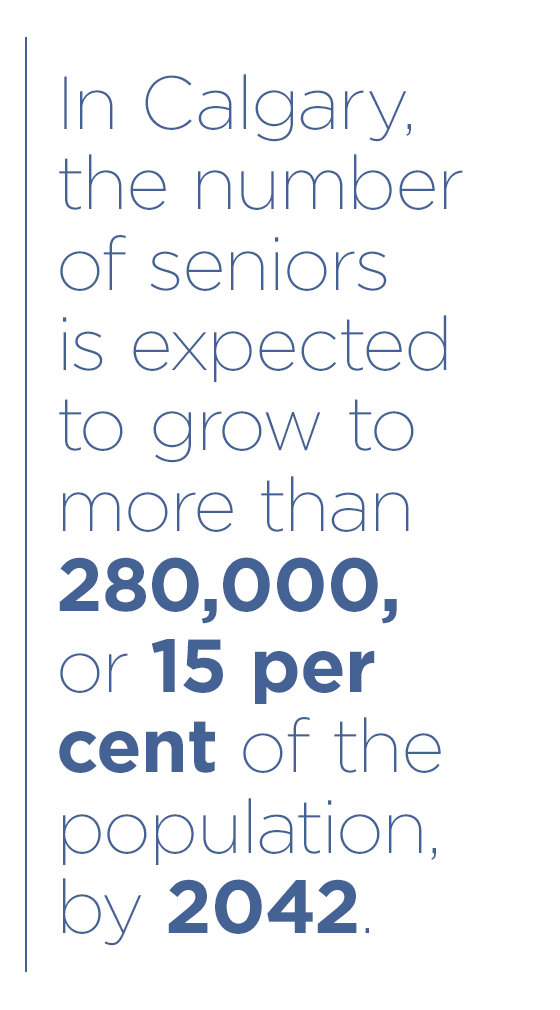

The statistics are daunting. Over the next 20 years, Canada’s seniors’ population is expected to grow by 68 per cent. The 75-plus age group will double, including in Alberta where, by 2038, more than 1 million Albertans will be over the age of 65. In Calgary, the number of seniors is expected to grow to more than 280,000, or 15 per cent of the population, by 2042.

We’re in uncharted territory. Caregiving is just one slim tributary in a vast network of social undercurrents driven by an aging population. While the House of Commons has declared a national climate “emergency,” no such designation has yet been afforded the potential stormy weather brewing alongside an aging population.

According to Calgary’s Aging Population Report, the city of Calgary is “on the edge of a rising tide of seniors” that will impact our communities, challenge the way services are delivered, and alter housing and support services, health services, recreation, transit and more. And these changes will not just impact this city, but communities across Canada.

So, what’s the plan?

The City of Calgary’s Age-Friendly Strategy, launched in 2015, has a focus on seniors and includes UCalgary faculty on the steering committee. There’s a federal Ministry of Seniors Canada. The Province of Alberta has its own Ministry of Seniors and Housing. Quebec even has a Minister Responsible for Seniors and Informal Caregivers.

Dr. Yeonjung Lee, PhD, an associate professor in UCalgary’s Faculty of Social Work, says preliminary findings from her ongoing research project to identify the concerns of older adults in Calgary show that aging communities have grown rapidly and spread across the city.

There is recognition that splintered services for seniors can be improved. A March 2018 report by a team of UCalgary researchers, presented by the Kerby Centre, focused on caregiver perceptions of support programs in Calgary. Creating a one-stop shop for caregivers to navigate available services was among its recommendations for community-support bodies to consider.

Is the system that serves seniors, their families and caregivers byzantine? Yes, given the sheer size and breadth of services. For housing alone, senior living and care arrangements span a wide range at varying costs, from independent retirement living (typically private-pay) and assisted living, to residential care homes, Alzheimer’s and dementia care in nursing homes, along with government-subsidized options such as supportive housing and long-term care homes.

When speaking to anyone involved in dealing with our aging society, including caregivers, it’s clear there are no quick solutions. Study is required to understand the varied problems and lay the groundwork for implementing practical solutions.

University of Calgary researchers, graduates and alumni are already on the front lines.

UCalgary at forefront of solutions for an aging population

Calgary Ward 3 Councillor and UCalgary alumna Dr. Jyoti Gondek, MA’03, PhD’14, knows well the tight squeeze that sandwich-generation caregivers feel daily — she’s one of them.

She’s got a 14-year-old daughter and an 80-year-old mother at home. As she zips from council meetings to home to her mom’s medical appointments to her kid’s school and activities, time is always tight.

“I’m the primary caregiver for my mom, but I have to prioritize like everyone else and it’s very difficult,” says Gondek, who earned her PhD in urban sociology and worked as the director of the Westman Centre for Real Estate Studies in UCalgary’s Haskayne School of Business before being elected to city council.

Today, Gondek’s mom has an appointment for knee surgery. Gondek needs to take her. If she does, Gondek misses an audit committee meeting. Cue sharp intake of breath. Multiply it throughout the day.

“Sometimes it just kills me, but I know I’m not the only one doing this,” says Gondek, who acknowledges that almost everyone over age 50 these days knows someone who’s ferrying kids and parents around town while dealing with an already crazy work schedule.

Gondek recognizes the city faces thorny problems with a growing senior population, yet she sees opportunities to get things right. While there is some fragmentation of City services, she says, efforts are underway to make improvements.

For example, the City and UCalgary have worked with other partners on the issue of housing affordability, Gondek says, referring to the Community Housing Affordability Collective (CHAC) that helps to identify gaps in services and how to address them. There has also been mutual work on the One Window initiative that aims to improve how Calgarians, including seniors, access housing.

Sometimes it just kills me, but I know I’m not the only one doing this.

— Dr. Jyoti Gondek, MA’03, PhD’14

Gondek says seniors would love to age in place, but Calgary needs to diversify its housing stock and be more creative. Today, for example, City approvals are required to build a secondary or backyard suite.

UCalgary’s School of Architecture, Planning and Landscape (SAPL), formerly the Faculty of Environmental Design, has presented the City with innovative advancements in aging-in-place laneway housing.

Technology including medical devices and health monitoring was part of the SAPL design for a one-bedroom, portable housing unit that could be temporarily placed in the backyard of a residential lot.

“Calgary was far behind in approving secondary suites in the home,” says Gondek. “I think we’ll get to the point where we understand laneway housing is a good thing for seniors and communities, but we’re still catching up on this idea.”

On a much larger scale, the University District is a new comprehensive, 200-acre community built on endowment lands owned by UCalgary. The mixed-use, multi-family development features The Brenda Strafford Foundation Cambridge Manor.

Slated to open for occupancy in mid-2020, Cambridge Manor will provide innovative aging-in-place living while being an integrated research and education facility in collaboration with the university’s Brenda Stafford Centre on Aging. The centre is a cross-faculty, interdisciplinary organization under the umbrella of the university’s O’Brien Institute for Public Health.

“Cambridge Manor will offer multiple levels of care to support aging in place,” says Brenda Strafford Foundation President and CEO Mike Conroy. “It’s one of the few facilities to offer the continuum of aging in place with supportive living and long-term care services.”

While Gondek applauds the development, she says there is always a concern to get the balance of affordability right. Not everyone can afford to live in seniors’ residences or cutting-edge developments, especially seniors and families who are disadvantaged.

Despite government programs and caring families doing what they can, when people fall through the cracks, where do they go?

UCalgary filmmaker works to protect the most vulnerable

Seniors age 65 and over are a slim portion of the adults who use homeless shelters in Canada, but they are the only demographic group for whom shelter use has increased over 10 years. As the number of seniors increases in coming years, it’s a fair expectation that the problem will get worse.

“Old-age pensions used to be a kind of saving grace for people, but social security hasn’t kept up with the housing and rental markets across the country,” says Dr. Victoria Burns, PhD, an associate professor of social work at UCalgary. “We’re seeing people over 50 becoming part of the homeless population that wouldn’t have in the past. There are long lists for social housing. We need more of it.”

The federal government’s announcement in 2017 of a $55-billion, 10-year national housing strategy is a timely investment into remedying problems, she says.

Burns, who has experience as a frontline social worker, combines academic know how with on-the-ground grit with her role as a documentary filmmaker. Her film, Beyond Housing, which she shot with the help of Calgary media artist Joe Kelly and released this year, focuses on seniors as they bounce in and out of homelessness.

“We can’t work in silos,” says Burns. “The health and housing sectors will have to work together so that people across the spectrum can get the right level of support at the right time.”

Housing is a social determinant of health, says Burns, having just returned to Calgary from showing her documentary film in New Zealand. “Without proper housing, seniors’ health will decline and they’ll become socially isolated, which can lead to even worse health.”

The social links that connect us

If life is one lengthy marathon, how do we best get to the finish line once we become seniors?

Dr. David Hogan, MD, a UCalgary professor who has been at the forefront of geriatric medicine research, says one of the main challenges posed by the wave of aging seniors is advising them on how to remain as healthy as possible and financially secure so they can live a meaningful life. There is an element of personal responsibility that will require foresight, planning and perseverance.

“If you’re age 55 now, you may live another 40 years. You have to ask yourself, ‘What can I do now to enjoy the last third or more of my life?’” says Hogan, who was the Brenda Strafford Foundation Chair in Geriatric Medicine at UCalgary for 25 years and is now the academic lead of the Brenda Strafford Centre on Aging at the university. “We need to start thinking about it early, consider how we treat our bodies and minds, stay engaged in society and life and activities that you find rewarding.”

The importance of physical activity and the role it plays in overall health can’t be overstated, especially for vulnerable populations, says Dr. Meghan McDonough, PhD, an associate professor and researcher in the Faculty of Kinesiology. Activity contributes to keeping people mentally and physically fit, allowing them to retain a degree of mobility and independence.

“I see the urgency of learning more about our aging population, and people’s particular experiences, so that we can determine how to help them,” says McDonough, who, in her research, is investigating the social supports that adults 55 and older have that keep them physically active.

UCalgary has put considerable weight behind this area of research. This study and others that the university is collaborating on with the City of Calgary — there are at least five of them ongoing — will translate into practical applications and recommendations on how to move forward, she says.

Making the mind-body connection is another key to promoting good health.

We need to start thinking about it early, consider how we treat our bodies and minds, stay engaged in society and life and activities that you find rewarding.

— Dr. David Hogan, MD

With demographics changing globally, there will be an increase in dementia and other diseases of the brain. Each year, 25,000 Canadians are diagnosed with dementia, and, by 2030, that number is expected to be just shy of 1 million. Led by the Hotchkiss Brain Institute, UCalgary has more than 200 researchers engaged in brain and mental health research.

The Alberta government launched a strategy for addressing the impending epidemic of dementia in 2017, including plans to improve the primary care system’s ability to manage patients and better educate the public. More than 42,000 Albertans live with some form of dementia; that number could triple to 155,000 if nothing is done, says the strategy.

Dr. Marc Poulin, PhD, a Cumming School of Medicine professor, and a research team from UCalgary conducted Brains in Motion, a study that focused on the links between lifestyle interventions — such as diet and exercise — and sleep and cognition. The findings showed regular aerobic activity can lead to declines in anger, confusion, depression, fatigue and tension.

The follow-up study led by Poulin, the Brenda Strafford Foundation Chair in Alzheimer Research, is Brain in Motion II. This study explores the connection between physical activity and cognition in adults who may be at risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease or another related form of dementia.

Signs of the times

There are signs, literally, that the health-care system in Alberta recognizes that caregivers need help. Taped to the wall of a room at Bowmont Medical Clinic in Calgary, where UCalgary medical students train and graduates work, there is a poster that reads: “Learn how to recognize that, in order to care for a loved one, you must learn to care for yourself.”

The sign promotes COMPASS for the Caregiver, a free nine-session weekly workshop launched last year, offered by the Calgary Foothills Primary Care Network.

Primary care networks streamline patient access to primary health care. Within these networks, groups of family doctors work with Alberta Health as part of the province’s public health-care system.

“The great thing about the workshop is that it’s peer-led by dedicated people who have been caregivers themselves,” says Allison Fielding, director, service delivery, for the Calgary Foothills Primary Care Network.

Andrew Hanon, acting spokesperson for Seniors and Housing Minister Josephine Pon’s office, says the province is working to improve access to supports for seniors and Albertans with low income, while eliminating red tape, duplication and non-essential spending.

“Financial benefits are available to help seniors with low income meet their basic needs, make adaptations to their homes, afford personal and health supports, and more,” Hanon says. “The government has committed to maintaining these benefits.”

Moving forward, we’ll need to strike a balance between what the health-care system can provide and what the family can do to support its members.

“It’s not always easy to strike the most appropriate balance, and we will need to be flexible,” adds Hogan. “Most family members are happy to assist a family member to live a fruitful, productive life, as long as it doesn’t get excessive. You can’t expect people to function every day as heroes, sacrificing themselves and their aspirations.”

Meanwhile, Vivian Coles, caring for her mom while balancing her home and work duties, believes the time for everyone to start discussing the impacts of an aging society is now.

“Our situation with my mom has opened up discussions with friends and peers,” she says. “My husband and I have discussed what will happen with us. At the end of the day, as we all age, we have to ask ourselves: ‘who is going to care for whom?’”

At the end of the day, as we all age, we have to ask ourselves: ‘who is going to care for whom?’

— Vivian Coles

Magazine | Fall/Winter 2019 | Who will help mom?

Explore more

Who Will Help Mom?

Over the next 20 years, Canada’s seniors’ population is expected to grow by 68 per cent and we, as a nation, are not ready. In fact, experts say we are facing a multifaceted economic, social and health-care crisis as our elder population grows. What are our priorities and what is UCalgary doing about the splintered system that exists today?

2019 Arch Award Recipients

Meet six remarkable alumni who are blazing trails across our skies, creating spaces for us to marvel at, championing rights for Indigenous people, leading coalitions of people, innovating new tech platforms and building bridges across global organizations. Although this year’s recipients walked the red carpet at the recent Arch Awards, their stories bear a replay.

Notebook

How did alumna Susanne Craig, BA’91, Hon. LLD’19 go from being a campus newspaper reporter to winning the Pulitzer; why language is critical, especially in the LGBTQ2S+ community; alumni star in a new movie; what, exactly, is Rococo Punk?

Can't Get Enough?

Take the ultimate tour of campus with President Ed McCauley, meet the 2019 Arch Award recipients and find out what UCalgary is doing about the coming health-care crisis as our elder population grows. All this and more in the Fall/Winter 2019 Alumni Magazine.